On the art of shortening literary texts

2 Sept 2024

Literary scholar Carlos Spoerhase brings abridged versions in from the cold.

2 Sept 2024

Literary scholar Carlos Spoerhase brings abridged versions in from the cold.

What was Schiller’s drama Wallenstein actually about? Browsing through a summary version could help answer the question. And that is no reason to be ashamed, if you ask literary scholar Carlos Spoerhase. The Chair of Modern German Literature at LMU has just finished writing a book on abridged versions and the role they play in literary culture.

© LMU/Florian Generotzky

Why are summaries of literary works so popular?

Carlos Spoerhase: We live at a time when people’s attention span appears to be shrinking. We have less and less time to read voluminous books. That is why all kinds of different attempts are made to find shortcuts that make longer literary works and even non-fiction books more accessible.

It starts with summaries of classic German literature – such as Der Zauberberg (The Magic Mountain) – acted out by toy figures in two-minute videos. But there are also more serious variants, of course: Major novels retold as audiobooks, for example. Or firms such as Blinkist, which lets readers get the gist of any book in 15 minutes.

Lately, generative artificial intelligence (AI) has likewise been added to the mix. Essentially, you can feed a 20-page scientific paper into ChatGPT and have a condensed version produced to meet your individual needs. It is also possible to have a text summarized using language a twelve-year-old would understand.

Condensed versions have played an important part in literary culture since ancient times.Carlos Spoerhase

If abridged versions are so widespread, how does that change the way we see literature?

This is the question that preyed on my mind a lot as I was writing the book. At first glance, you would say that reading a summary is an attempt to perceive the book not as an aesthetic whole, but only to pick out bits and pieces that let you – at a party, for example – pretend you have read the whole thing. That said, after spending a lot of time researching the history of abridged versions, it became clear to me that things are not that simple. Condensed versions have played an important part in literary culture since ancient times.

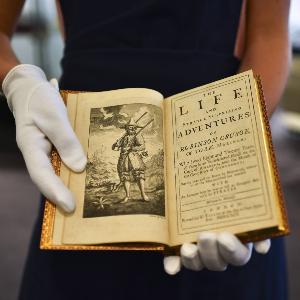

photographed at a Sotheby auction in London in 2019. | © IMAGO / ZUMA Press / Alberto Pezzali

In your book, you say that most of us only know Robinson Crusoe, for example, in an abbreviated form. Why is that so?

As far back as the 18th century, three quarters of all editions of Robinson Crusoe that were in circulation were already abridged versions. Sometimes this was plainly declared, sometimes it wasn’t. In other words, most of the people who read Robinson Crusoe in the 18th century or later had a condensed version.

For example, the original work contains very protracted theologically motivated passages, and these were eliminated in the abridged versions. And it was this shortening of the work that for the first time made Robinson Crusoe a modern adventure novel that revolves heavily around a plot and a main character who has certain experiences and is confronted by certain obstacles.

Robinson Crusoe thus became an adventure story through the back door, so to speak. And because it was and is so successful, it played a huge part in establishing this new literary model. That is not something the author did himself. Rather, it was the fruit of anonymous individuals who produced these abridged versions. In most cases, we do not even know their names.

So, this was a distinctive work by those who did the shortening?

Yes, it is a distinctive work. And it is important to make that point. Why? Because only in the recent past – literally in the last few years – have we seen literary scholarship paying more attention to the intermediaries who have contributed to the production of a text. These include lectors, but also individuals within the author’s closest circles, many of whom read and annotate initial drafts. This entire collaborative dimension of literary production is only gradually coming to light. And the people who abridge texts are part of this collaborative process.

You go so far as to call them “reduction artists”.

Yes, it really is an art form. And this is a question that also extends beyond the realms of literature. Think about the role of the trailer in motion pictures: How do you pack a 90-minute Hollywood film into a three-minute trailer?

There is certainly a democratic aspect to condensed versionsCarlos Spoerhase

Have abridged versions contributed to the wider dissemination of literary works?

There is certainly a democratic aspect to condensed versions. People for whom the original literary works are inaccessible due to their level of education or other circumstances can approach them via summarized versions. One reason is that summaries are materially produced in such a way that they are less expensive. But condensed versions also play an essential role regarding the issue of how much attention must be invested and what educational requirements must be met in order to grasp certain issues.

Literary culture must be understood as a kind of text ecology in which different text formats circulate and are intertwined. That happens in the perceptions of readers, too.Carlos Spoerhase

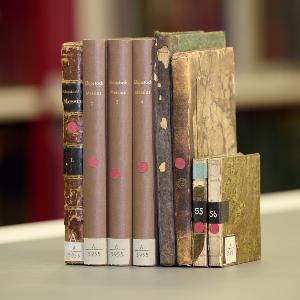

has almost 20,000 verses. The first abridged version was written as early as the 18th century. | © Carlos Spoerhase

Abridged versions nevertheless appear to be seen in a dim light in the education context. Why?

Yes, sadly, that is true. The debate was sparked off back at the start of the 20th century. At that time, the idea of discussing literary works in abbreviated forms in schools was vehemently rejected. The belief was that schoolchildren should either be able to read a work in its entirety or they should leave it. And you can trace the same discussion right up to the present day – for example, when the influential German daily FAZ asserts that whole texts are no longer read in schools, and that this is the reason why literary culture is doomed.

I would say that that is wrong. There are good ways of assimilating texts in condensed form. That is not to say that they should replace full texts. But I do believe that abridged versions assume an important mediating function, and this fact is cast aside when you assume the cultural maximalist position. Literary culture must be understood as a kind of text ecology in which different text formats circulate and are intertwined. That happens in the perceptions of readers, too.

Who actually authorizes these abridged versions?

That has been one of the big problems since ancient times. One of the first remarks about abridged versions that has been preserved comes from the ancient physician and scholar Galen (born around 129 AD in Pergamon), who noted that so many unauthorized abridgments of his works were circulating that he felt compelled to create his own, even though this really wasn't what he wanted.

Authorization is always an issue. In the 18th century, a teacher asked the German poet Klopstock for permission to produce a short version of one of his works and disseminate it in print for educational purposes. Klopstock asked to be able to review the manuscript of the abridgment but did give his consent. I am sure that the writer felt uneasy in doing so. On the other hand, he was aware that literary texts can be incredibly difficult and demanding, and that it can in no way be taken for granted that people will read them and immediately grasp their meaning.

I believe that one crucial task of literary teaching in schools, but also at universities, is to cultivate a feel for such aspects and an aesthetic awareness.Carlos Spoerhase

AI now lets people produce their own summaries. So why even bother to read an entire work anymore?

There are obviously novels, epics, lengthy plays that you can only properly understand if you grasp their complex composition in its entirety. I believe that one crucial task of literary teaching in schools, but also at universities, is to cultivate a feel for such aspects and an aesthetic awareness.

That said, I also believe it often makes sense as a first step to use certain forms that give you an overview. Before launching into a sizable novel, for example, you can then get an initial idea of the main threads and characters. Then, in a second step, you may have less difficulty tackling the whole work and above all paying attention to aesthetic attributes, such as the language and its poetic usage.

“There are good ways of assimilating texts in condensed form“, says Carlos Spoerhase. | © LMU/Florian Generotzky

Can your book be understood as a kind of plea on behalf of abridged versions, then?

It is an attempt to examine the functions of condensed versions and our understanding of what constitutes a successful version for specific purposes. It is also an attempt to remove the taboos associated with abridged versions and bring them in from the cold. For example, literary scholarship is familiar with encyclopedias of literature, which typically also contain summaries of works. And these are, of course, very frequently used in journalism, at universities and in other cultural contexts. Or, before going to the theater, to familiarize yourself with a plot of which you only have vague recollections. We just don’t talk about this practice very often, so it evokes a measure of shame because people think: I really ought to know that, I should have been able to remember it. We need to be a little more honest and admit: We use these tools! They are obviously not the whole work. But in certain contexts they serve an important function, helping us to navigate the cultural sphere, to prepare ourselves and free our minds to focus on aspects of aesthetic relevance – such as when you go to the theater and watch Schiller’s overwhelming Wallenstein trilogy.

So, you yourself make use of abridged versions?

Yes, I do.

Carlos Spoerhaseis Chair of Modern Literature, his main focus being on the literature of the 18th and 19th centuries. He studied modern German literature, philosophy, and political theory at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin (HU Berlin), where he also earned his doctorate. He then worked as a research associate at the University of Kiel and HU Berlin, qualifying as a professor at the latter institute. After holding professorships at the University of Mainz and the University of Bielefeld, Spoerhase took up his present appointment at LMU in 2022. Key areas of his research include the sociology of literature and the history of the humanities.

Carlos Spoerhase: Kurzfassungen. Über das Komprimieren von Literatur. Wallstein Verlag 2024